Do you still have your kids’ baby teeth in the back of the jewelry box somewhere? Does your mom still have yours? Do you know there was a time when baby teeth changed world political policy? It all goes back to the 1940s-1950s.

The first nuclear bomb test blast was in 1945, at White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico. The atomic bomb drops over Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed soon after. Over the next ten years, the US conducted almost 200 nuclear test blasts, mostly in New Mexico, Nevada, and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific. Those tests left significant radioactive waste in the atmosphere, which spread with wind and rain across the US and the world. Eventually, people began to worry about exposure to this radioactivity.

In 1958, an article in the British scientific journal Nature explained that strontium-90, present in radioactive fallout in wind and rain, gets into plants, and ground water, as well as the air. It then finds its way to cows, milk and finally, human bones and teeth. The article suggested studying baby teeth as a marker for exposure to radioactivity. A grassroots initiative, mostly led by women community leaders in St Louis, Missouri came together and created the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information. In conjunction with Saint Louis University and the Washington University School of Dental Medicine, they developed a research study using baby teeth.

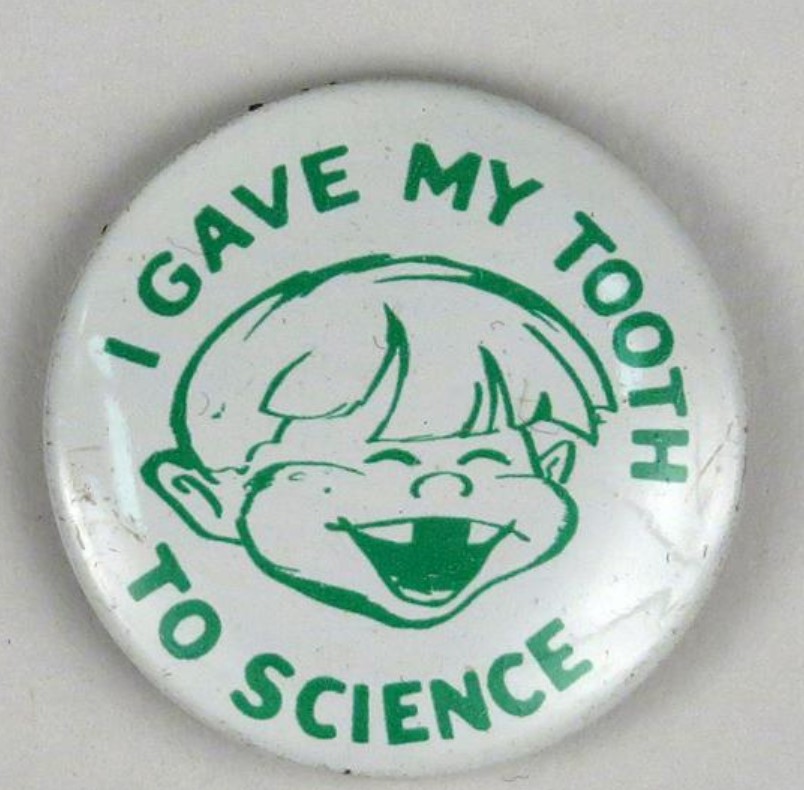

Now, baby teeth begin developing at 14 weeks of prenatal age, and continue through a child’s third year of life. So, this project needed to happen quickly because they needed a baseline of baby teeth from children who were 3 years old or older in 1945, before any exposure to radioactive fallout. Since people lose baby teeth when they are 5-8 years old, they needed teeth from people born from 1942 onward. They could then compare those teeth to others shed after 1945, when nuclear testing began. The team created a cute pin and certificate for tooth donors, and got the help of scout troops, garden clubs, YMCAs, schools, and dentists to get the word out. Tooth collection boxes were set up in libraries, schools, drugstores, and dentist offices. Proud tooth donors got their distinctive pin, and filled out index cards with demographic information.

Thousands of teeth were collected from St Louis and surrounding areas. The project collected and catalogued almost 15,000 baby teeth in its first year. Their study, published in 1961, showed that radioactive strontium-90 levels in the baby teeth of children born from 1945 to 1965 had risen 100-fold and that the level of strontium-90 rose and fell in correlation with atomic bomb tests! At the same time, a U. S. Public Health Service study showed an alarming rise in the percentage of underweight live births and of childhood cancer. When this information was made public, anti-atomic testing protests increased. The results of the study were sent to President Kennedy, and persuaded him to negotiate a treaty with the Soviet Union to end above-ground atomic bomb testing in 1963. The LTBT (Limited Test Ban Treaty) was the first arms control agreement of the Cold War.

By the end of the Baby Tooth Survey in 1970, almost 300,000 teeth had been collected and analyzed. But the story doesn’t end there.

In 2001, a biology professor at Washington University was looking for more storage space and came upon a forgotten set of 85,000 teeth. Calling the Radiation and Public Health Project (RPHP), he said, “You better sit down, there are thousands and thousands of teeth there.” Washington University donated the teeth to RPHP, and the research continued. By tracking 3,000 individuals who had participated in the tooth-collection project, the RPHP published resultsthat showed that the 12 children who later died of cancer before the age of 50 had levels of strontium-90 in their stored baby teeth that were twice the levels of those who were still alive at 50. This study is controversial, as correlation doesn’t prove causation, and there were other ways those teeth (and children) could have been exposed to radiation. Yet it is one of the few longitudinal studies that follows children over many many years. This study, the St. Louis Baby Tooth – Later Life Health Study, now based at Harvard, continues today, investigating the long-term effects of early life environmental exposures.

RPHP is encouraging more research with this treasure trove of teeth. “You can use teeth to measure fluoride and pesticides, conduct research in genetics, anthropology, and dentistry and many more things.”

In fact, baby tooth research is happening elsewhere. You may have heard of Dr Hanna, the Flint, Michigan pediatrician who was instrumental in publicizing the problems with lead in the Flint water supply. She is now spearheading the Flint Tooth Fairy Project, to study lead levels in baby teeth from Flint children born between 2011 and 2015. Since tooth development starts before birth, and enamel is laid down in teeth like rings in a tree, the timing of lead exposure can be calculated fairly well, including pre-natal exposure. Small gold mines in Africa use mercury in processing the gold. Baby teeth studies are now going on there, to understand mercury exposure in children near gold mines. Both lead and mercury are significant neurotoxins.

And if you aren’t impressed enough about the value of teeth, let’s talk about wisdom teeth, more properly known as third molars. About 85% of Americans have at least one wisdom tooth pulled, a total of ten million teeth a year. These teeth are typically thrown away. Well, as it turns out, the dental pulp of wisdom teeth is a rich source of stem cells, which can, in the lab, be coaxed to regenerate into various specialized cells. Regenerative medicine is a hotbed of research now, with attempts to make new corneas, cartilage, and other types of tissue. There is promising research showing that these pluripotent (able to make many kinds of cells) stem cells may be important for treatment of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, heart failure and other diseases.

Many parents now bank their newborn’s cord blood, because of the stem cells there. Those stem cells can be used to make blood cells. Wisdom tooth stem cells are different and could potentially be used to make many types of tissue. Being able to use cells made from your own tissue avoids the problems of tissue matching, rejection, and waiting for an organ donor. Of course, there are companies willing to bank your child’s wisdom teeth, as research progresses. It’s all research now, but at some time in the future, there could be a good reason to save wisdom teeth. As one of these companies says, you might want to join “thousands of forward-thinking people who have taken control of their family’s future health”.

Just think about it. Those teeth you once threw away may be good for something after all!

PS. If you used to live in St Louis and you or your mom donated your teeth in the 1950-1960s, Harvard is looking for you. They’ve found about 5,000 of the original tooth donors and are always looking for more. Interested in their research? Look here.

Your stories always make me think. I remember going out to the place in white sands and not staying because of all the security stuff. Is it open to visitors? It didn’t seem so , but my memory is fuzzy. I don’t think my family knew about the baby teeth collection. The Walker family could have donated 100 + teeth. I wonder where they disappeared to. Who knows what other experiments we baby boomers are a part of.

Great piece, Ann, and a wonderful example of community-based research at its finest. I am very interested in whatever other findings those researchers will reveal in the future.

An interested reader sent a link to this related article. Fascinating and horrifying. https://lost-in-history.com/the-conqueror-the-movie-that-killed-actor-john-wayne/