If you’ve ever tried to hold a flashlight for someone while they work under the hood of a car, you understand the importance of good lighting. The inside of a human body is a dark place, and surgeons need a lot of light to see what they are doing. Ever wonder how surgeons saw what they needed to see before electricity, and how those fancy lights were developed?

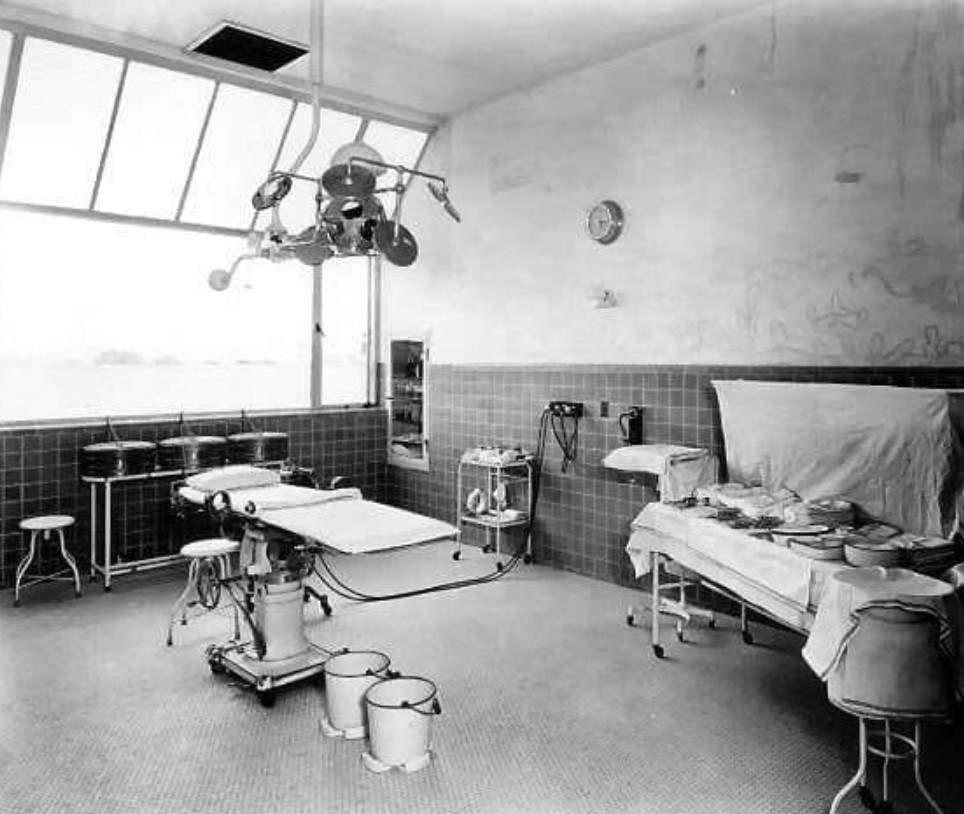

In ancient times, surgery, as rudimentary as it was, was performed outside, ideally under bright sunlight. As time progressed, and operating rooms were developed, the direction of the sun was taken into account in construction. Operating suites were built facing the southeast, for the best light exposure. Typically, they were on the top floor of the building, where large walls of windows or skylights could be built to maximize the light entering the room. Operating tables were positioned for the areas directly under the sunbeams and surgery was usually timed to occur between 10 AM and 2 PM, with the sun overhead. Mirrors were often positioned in corners of the ceiling to reflect light appropriately. Some time later, someone had the ingenious idea of hanging a multitude of mirrors from the ceiling of the operating theatre, to allow sunlight to reflect onto the operating field.

There were obvious drawbacks. Cloudy or stormy days were problematic, as were nighttime emergency operations that could not wait until daytime. Then, the flickering light of candles and lanterns was deployed, to some effect. However, the constant problem was that surgeons, leaning closely over the patient, created dark shadows and obscured the view. And none of these methods really got bright light deep in body cavities.

By the 1890s, most hospitals had gas lights in operating rooms, providing a brighter, more consistent light. Gas lighting was a temporary improvement, but the danger of gas explosions and the problem of open flames near flammable material in the OR, were significant drawbacks. During this time period reflectors were developed to enhance the brightness. At least gas light allowed for longer surgeries, and nighttime surgeries.

Edison’s development of the first practical filament light bulb in 1879 led to rapid innovations everywhere, including hospitals. By the late 1890s, generators and electricity distribution stations existed, and operating rooms were installing filament light bulbs, as they became more dependable and safer with time. Those light bulbs were the equivalent of one of today’s 25-watt bulbs. A vast improvement, but still dim by today’s standards, right?

And here’s where the snow globe makes an appearance. It was 1900 when Erwin Perzy, a tradesman who built and repaired surgical instruments for local physicians in Vienna, was tasked with creating an inexpensive solution to amplify light in hospital operating rooms. Perzy began searching for ways to increase the light produced by the light bulbs while making them cooler at the same time. He remembered that, for hundreds of years, shoemakers and other craftsmen used schusterkugels (cobbler-spheres), glass spheres with a tubular end filled with water, to magnify and redirect candlelight into a concentrated beam. They were primitive spotlights. Perzy experimented with schusterkugels, but the light was still not bright enough. He added various substances to the water to reflect and intensify the light such as flakes of metal and fine glass particles, but they quickly sank to the bottom. He even tried rice and flakes of a coarse flour called semolina, but none produced a brighter light for more than a second or two. He was never able to invent anything that really produced a brighter light for his surgeon clients. A failed experiment. Except that he realized the semolina flakes looked like snow. He kept tinkering. He had friends who sold souvenirs to pilgrims at a local church, and he made little pewter models of the church for them. One day, he combined a little model of the church with a glass globe full of water and white wax flakes (snow), creating the first snow globe. These globes were an immediate hit. He patented the little globe, and the rest is history. The Perzy company, now in its fourth generation, sells over 300,000 snow globes a year. And the makeup of the “snow” in the globes is a proprietary secret. Not bad for a failed operating room light experiment!

It was in 1919 that Professor Louis Verain from the Faculty of Science in Algiers designed the “Scialytique” (from Greek, meaning without shadows), one large lamp with multiple lights and mirrors and reflectors, offering a concentrated, directional field of light that eliminated almost all cast shadows. This is the big overhead, ceiling mounted light that would look familiar to you today.

This was a significant step forward, but those incandescent bulbs generated significant heat. Remember, this was before air conditioning, and fans could not be used in operating rooms (for fear of stirring up dust or germs that could fall into the operative site). Surgeons and nurses wore heavy cotton scrubs and stood under those hot incandescent lights. The surgical team wore small bags of ice on long strings around their neck, hanging against their chest and back, under their scrubs, to keep them cool. My mother was a student nurse in the 1940s. She remembered that one of her duties in the OR was to mop the surgeon’s brow (to avoid sweat dripping onto the patient), and to replace the ice bags when they melted, during long operations.

By the 1960s, the incandescent bulbs were replaced with new halogen technology, much whiter and brighter, but still hot. In the 1980s, reflection technology brought about a groundbreaking improvement; specially developed mirror and lens systems bundled the light evenly and reduced shadow formation to a minimum. In addition, the development of sterile handles made it possible for a surgeon or nurse to reach up and reposition the surgical light during a procedure without compromising sterility. In the following decades, the halogen bulb used different gases such as mercury and sodium, and certain lamps in the 1990s were even able to achieve a two-fold increase in illumination. Xenon lights came next, with bright, white light and better color differentiation. In the 1990s, these lights were replaced by light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which are cooler, have reduced energy consumption, and a compact design. These are still used today.

AI is even getting in on the game. Work is in process using AI generated algorithms, so surgical lighting can vary based on learned surgeon preference and the type of tissue being illuminated.

And what about power outages? You’ll be relieved to know that if you are on the operating table when the power goes out, hospitals now have backup generators that switch on in seconds, automatically sending uninterrupted electricity to critical equipment like operating room lights, ventilators, and oxygen compressors.

Most operating rooms don’t even have windows now, since everything depends on electricity. It’s a far cry from waiting for the sunlight, isn’t it?

These are always very interesting

One comment I think you meant Edison invented the first practical filament light bulb not Einstein.

Ugh!! No matter how many times I proofread these, silly mistakes creep in! Thanks for spotting this! Ann

From a reader:

Splendid, as always. I presume, though, that you mean “Edison” rather than “Einstein,” right?

I spent a summer in medical school with a community practitioner. He had spent time volunteering with Project Hope, and I asked him for details. He said the main thrust was improving operating rooms in third world countries. I found that strange for a pediatrician and pressed him. The operating rooms were arranged as you describe, capturing sunlight. The problem Project Hope addressed was the open air arrangement, and the improvement was to install screens on the windows.

Keep the newsletters coming! I love them.

Once while performing a procedure in a rural clinic the power went out and we quickly donned our battery powered headlamps routinely used by outdoor enthusiasts. They worked really well.Bright, adjustable LED light that follows the field of gaze. No generator required. I always have a few in my mobile med kit.

Fascinating! I’m thankful that I didn’t live in the 1800s and need an emergency appendectomy at night.

Thank you for illuminating us about OR lighting (or lack thereof). 🙂

Scary to think about it, isn’t it?

Appreciate you putting a little light on the subject. I wonder how many patients had wax drip into their chest cavity during surgery. I’m sure you are never at a loss for topics, but I’d love to know the “rest of the story” about the man or the team who invented eye glasses and then contact lenses. I thank those people every day for those inventions.

Great topic! I’ll add it to my list.

Fascinating! And what a sweet back story to the beautiful snow globes that I still love 🙂